Tycho Brahe - The story of the Danish superstar astronomer

Tycho lived in the 16th century, and made astronomical observations far more precise and extensive than had been made before. These observations ultimately led to the discovery of the true dynamics of the solar system.

Tycho Brahe is often disparaged as a guy who wouldn't accept the conclusions of his own observations, and stubbernly held on the the idea of an Earth-centric solar system. However, the real scientific history is more nuanced; more on that later.

When Tycho was young he had a duel with a fellow nobleman over who was the better mathmatician, in which he lost part of his nose. He wore a prosthetic nose for the rest of his life. On special occassions he would use one made of gold.

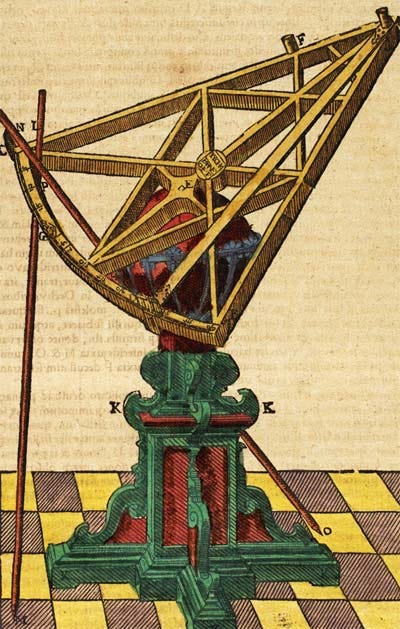

Living before the invention of telescopes, Tycho made his precise measurements by building an observatory underground for stability and creating customized, extra-large sextants and other instruments.

He observed and described supernovae, coining the term "nova" and noting that they must be beyond all the planets. This observation was a significant departure from the prevailing belief that the world beyond the moon was eternally unchangeable.

Tycho was a strong critic of the Earth-centric Copernican system for two main reasons. One was that it did not fit the observations very well, especially with his more precise ones. This was partly due to the rigid belief that the movements of the planets were circular. Instead, Tycho proposed the Tychonic system, in which the Sun and the Moon revolve around the Earth, and the planets revolve around the Sun. This was not a great fit with the observations either, but it was neither much better nor worse than the Copernican system.

He had another major reason for preferring the Tychonic system though, which interestingly was sensible given the data he had at the time. One can observe that the distance between stars in the sky stay constant, even from different places on the earth. This must mean that the stars are further away than the planets. One can then use the visible size of stars on the sky and compare them to the size of closer objects, and deduce that they must be larger than the moon, although they appear much smaller. This is fine. But if you accept that the Earth revolves around the sun, then the logic applies not only to different places on Earth, but to different places on the Earth's orbit, which would mean that the stars were exceedingly far away (which is indeed the case).

But here comes the tricky part: Applying this logic with the observations of the size of stars they had at the time, would imply that all the visible stars are not just sun-sized, but that all are much larger. The reason that the logic works out like this, is that due to the complex dynamics of light, the visual size of a star on the sky is larger than its actual size. But these light dynamics were not discovered until long after Tycho was dead. So calculations made in the intuitive way at the time, presuming that the observable size corresponds to the real size for stars as well as for planets, would find that all visible stars are larger than the sun. And Tycho was right to find this absurd. To have a universe with a number of stars of sizes smaller and larger than our sun makes sense. But to have a universe where all stars dwarf our own sun in size is weird.

The Copernicans didn't have a good counter-argument to this, resolving to ~"God is great and can do whatever he wants. He can make the heavens filled with enormous heavenly bodies." But in this argument Tycho was right. All stars are not in fact larger than our sun. This shows how sometimes in science you can make correct arguments, but turn out to be wrong nonetheless.

After Tycho’s death, his student Kepler used his precise observations to discover the laws of planetary motion, showing that planets moved in ellipses, which fit the observations so well that a Sun-centered model became undeniable. Later, Newton built on the work of these two giants to discover the laws that connect the heavens and the Earth.

After many years of successfully running the observatory, Tycho was forced to leave Denmark by a new king, Christian IV, who was eleven at the time. The king’s men, sent to collect what they could from the observatory, wrote back about the brilliant custom-made instruments that they were "useless or harmful".