Twin studies show that parenting doesn't matter that much

Parenting has limited influence on personality traits and life outcomes.

I often see my peers anxious about many aspects of child rearing, convinced that many everyday experiences will leave a lasting mark on their child’s future. They worry about the longterm psychological effects of things like watching tv, sustained crying, not reaching developmental milestones at certain times, receiving fewer moments of adult attention, and more.

These worries are misguided.

Decades of twin research demonstrate that parenting has limited impact on child outcomes. These results remain largely unknown even among well-educated audiences. This is true even though it represents mainstream science appearing in introductory behavioral genetics textbooks.

Understanding this could help free parents from unnecessary anxiety. Since most parents already provide good enough care, much of their worry focuses on factors that won't meaningfully affect their child's longterm wellbeing. They could worry less about these specifics and remain just as good parents.

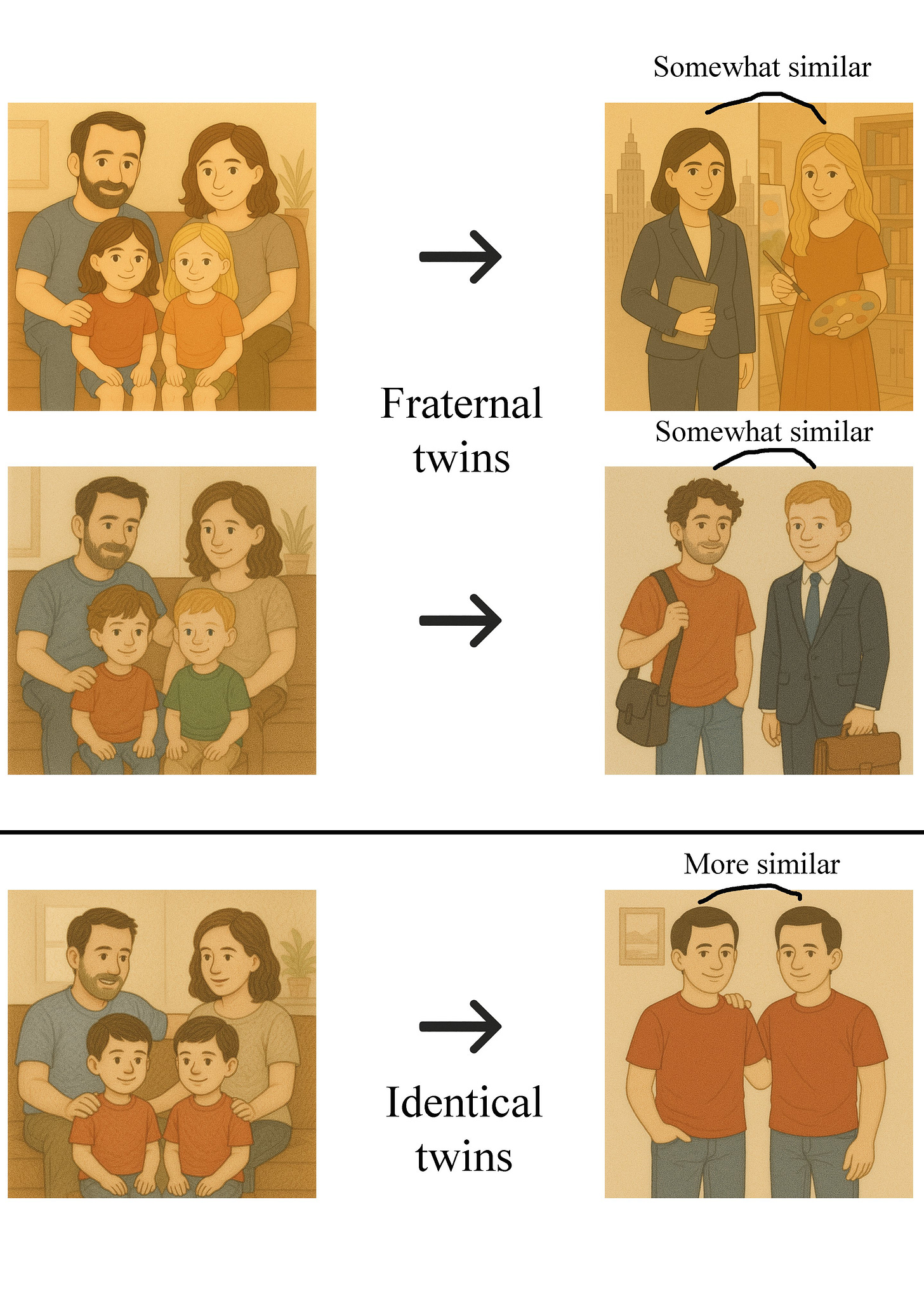

There are two major types of twin studies. The more straightforward type studies identical twins who were separated at birth and raised apart. These studies consistently show that despite growing up in completely different environments, such twins often display strikingly similar personalities, abilities, and behaviors as adults.

This is what people usually think of as 'twin studies'. However, identical twins raised apart are very rare, so the total sample size is not that large. But this is in fact not the main type of twin study. The main type of twin study uses normal identical twins who grew up together, and therefore has vastly higher sample size and scientific power. The Danish twin register alone has 13,000 identical twins.

The results from these studies depend on the trait studied; some traits are more heritable than others. But as a general rule of thumb, you can think of the overall results like this: Peoples' traits and life outcomes are shaped 50% by genetics, 40% by unique factors, and 10% by their childhood environment, including parenting.

In the section below I will explain in more detail how twin studies work, and how they arrive at these figures.

I find that the easiest way to understand twin study findings is through a two-step process: first establish how much genetics and childhood together explain, then separate these two factors.

Step 1 - The combined effect: Identical twins raised together are more similar than unrelated people, yet they still differ significantly. Studies show their scores on most traits correlate at about 0.6 on average. This means the factors twins share — identical DNA and identical family environment — together account for roughly 60% of population differences. In other words, genes plus upbringing explain about 60% of why people vary. If these two together explained more than that, the correlation between identical twins (that both have the same genetics and the same childhood environment) would be higher. The remaining 40% comes from randomness and factors unique to each individual, that cannot be influenced by parenting.

Step 2 - Separating genetics: Twin studies can isolate the genetic component by comparing identical twins (who share all genes) with fraternal twins (who share roughly half). Since both twin types experience similar family environments, any extra similarity in identical twins must stem from their additional genetic overlap.

This step uses some simple math. Let x represent the extra similarity found in identical versus fraternal twins. Since x reflects the boost from one additional half-share of genes, a full genome would provide 2x similarity. Researchers typically measure x at about 0.25, so 2×0.25 equals 0.50. This means roughly 50% of individual differences trace to genetic variation.

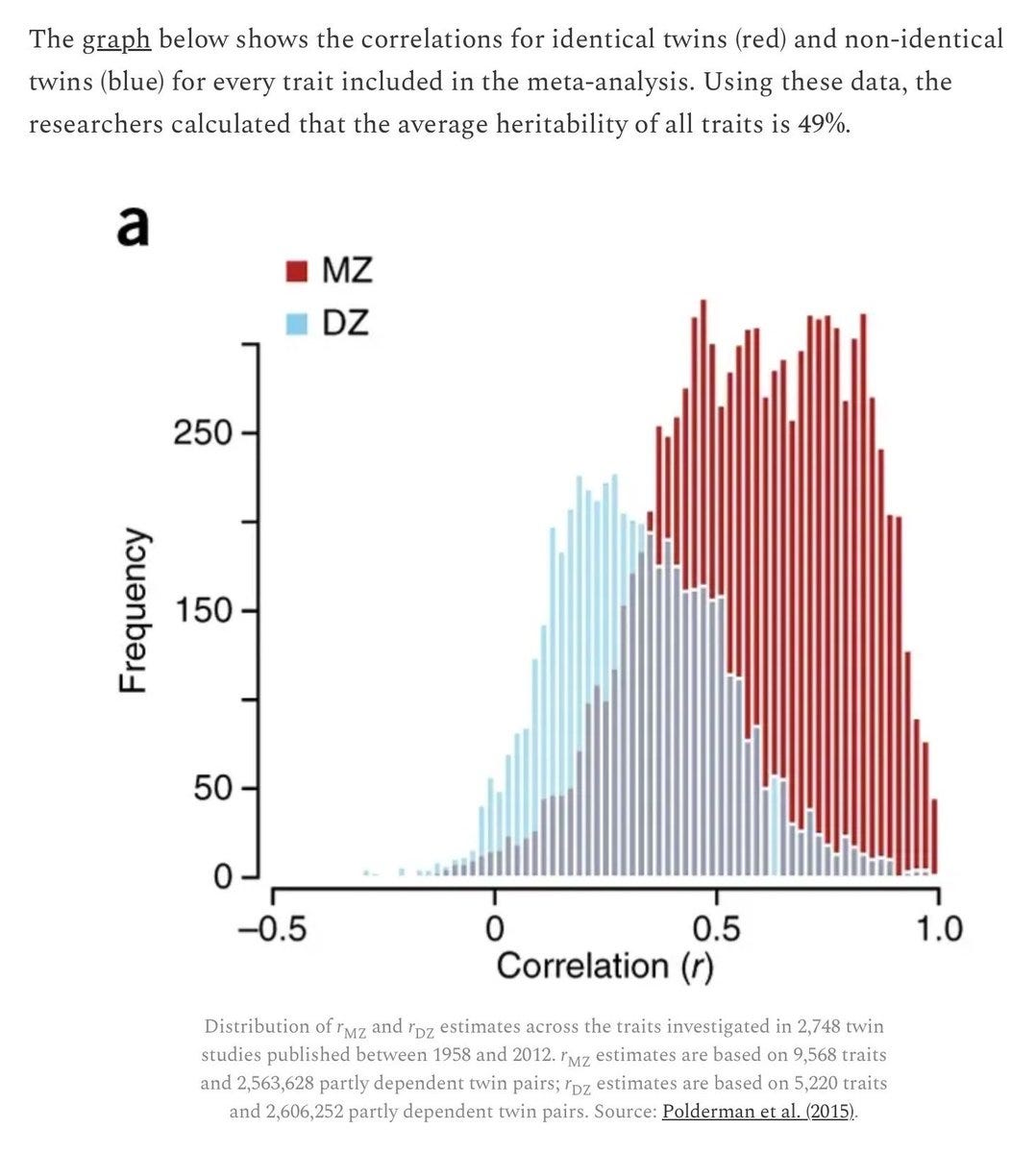

Real-world evidence: The bar chart below confirms this pattern. Light-blue bars show fraternal twin similarity across various traits, while red bars show identical twin similarity. The average gap is about 0.245, and doubling this gap yields a heritability of 49% (roughly 50%).

Now we can address the key question: how much does childhood upbringing matter? We found that genes plus shared childhood explain about 60% of population variation, while genes alone explain about 50%. Subtracting the genetic share leaves roughly 10% attributable to the family environment siblings share.

That is: Children's personalities and lives are mostly formed by their genes and by random factors, and how you raise them has little influence.

Comments and caveats:

• As mentioned, the percentage figures (50% genetics, 10% childhood environment, 40% other) are an overall rule of thumb. Individual traits and life outcomes can have larger or smaller values. For many traits, the importance of childhood environment may be closer to 0%

• The impact of parenting can be more significant in the short term, but these effects fade as children grow up. For instance, a parent who drills their child on math problems may boost the child's test scores temporarily, but this advantage typically disappears over time as inherited mathematical ability becomes the dominant factor.

• Twin studies measure the impact of behavior within a normal range. So for example, abnormal child abuse or neglect can have a larger impact.

• Some critics argue that parents treat identical twins more similarly than fraternal twins, which could inflate the apparent genetic effects. However, research by Conley et al. (2013) studied fraternal twins whose parents mistakenly believed they were identical. Despite receiving the more similar treatment typically given to identical twins, these fraternal twins showed no greater similarity than ordinary fraternal twins who were correctly identified. This suggests that differential parental treatment does not inflate the genetic effects found in twin studies.

• Recent research, such as that from Gregory Clark, indicates that there is very high assortative mating in the population. This would mean that the genetic heritability of traits is in fact even higher than estimated from twin studies.

Some sources:

Bouchard TJ Jr. et al. (1990). “Sources of Human Psychological Differences: The Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart.” Science, 250, 223-228.

Polderman TJC et al. (2015). “Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on 50 years of twin studies.” Nature Genetics, 47 (7), 702-709

Plomin R. et al. (2016). “Top 10 replicated findings from behavioral genetics.” Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11 (1), 3-23.

Ligthart L et al. (2019). "The Netherlands Twin Register: Longitudinal Research Based on Twin and Twin-Family Designs." Twin Research and Human Genetics, 22(6), 623-636.

Hilker R. et al. (2018). “Heritability of Schizophrenia and Schizophrenia Spectrum Based on the Nationwide Danish Twin Register”. Biological Psychiatry, 83 (6), 492-498.

Tucker-Drob EM & Briley DA. (2014). “Continuity of Genetic and Environmental Influences on Cognition across the Life Span: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Twin and Adoption Studies” Psychological Bulletin, 140 (4), 949-979.

Twin studies show the effect within a normal range of parenting styles. But don’t they also show the effect with a normal range of genetics among the twins? Isn’t it possible that parenting becomes more important for children with less common genetic vulnerabilities?

As a parent this feels so counter-intuitive.

I get the connection with genetic similarity looking like environmental influence (meaning that the inherited genes have a higher impact than the actual environment you grew up in, but people usually put things down to the environment they grew up in).

But here's my issue with this train of though:

"Things like "critical thinking," "emotional regulation," or "growth mindset" are often called teachable skills but probably have large trait components."

Even Claude tries to convince me that growth mindset is a trait, not a learnable skill.

I think this is dangerous. I'm not saying you can become a basketball player if you're 5" tall (except Muggsy Bogues). There's a limit to how we can mold ourselves.

But I think that limit already far too low for the regular person.

If this study helps people to worry less about parenting, great, but to me it doesn't appear very encouraging when it comes to human potential and how to nurture it.

So while the fact might be there, I intuitively disagree with the message.

I do believe you can learn things like a growth mindset. And that very belief might be the reason why I perform better than someone who does not belief that.

The other thing here:

A dysregulated nervous system can screw you over (that might be influenced by genetics too, like if your Mom went through a lot of stress and those genes activates).

Just fixing that will give you an insane increase in performance in both work and your social life.

My guess: If you're a capable parent you might be able to tap into a lot more of those 40% mentioned above shaped by "unique factors".

The same if you're a capable coach, manager, mentor.

So I respectfully say: Screw these studies.

Great work synthesizing this information, though. Very thought-provoking, Jonatan.

PS: Pushed this into my Kortex notes. I will pick this up again.