Origins of AIDS: The polio vaccine hypothesis

Reexamining a "discredited" theory.

Written by Jonatan Pallesen.

Last year, around 630,000 people died from AIDS-related illnesses worldwide. But where did HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, come from? Few people are aware that there exist two viable hypotheses for its origins in humans:

The bushmeat hypothesis. In the early 20th century, a person in central Africa caught the virus after being bitten by a chimpanzee or consuming chimpanzee meat. The virus then spread in humans unnoticed for decades, before eventually giving rise to the AIDS pandemic. This is the mainstream, accepted hypothesis.

The oral polio vaccine (OPV) hypothesis. In 1957–1960 there was a trial of an experimental polio vaccine in the Belgian Congo involving nearly one million people. This vaccine used kidney cells from chimpanzees, some of which were infected with a virus closely related to HIV. As a result, the virus crossed over to humans through the vaccine, giving rise to the AIDS pandemic.

It is widely claimed that the OPV hypothesis has been refuted, and that the vaccine used was not in fact contaminated with HIV-related viruses. However, this is not true. While other oral polio vaccine batches have been tested and found negative, the ones produced in the Belgian Congo in 1957–1960 have never been tested.

Background

It is important to understand the background to vaccine research in the 1950s. It was a different science that was much more unrestrained and reckless. It was common to kill primates and use their kidney cells in vaccines, with insufficient safety and control. Furthermore, the oral polio vaccine was a live vaccine, which made it hard to kill any contaminating viruses without also killing the polio virus. Hence there was a real risk of people being infected with primate viruses from these vaccines. This actually happened with another polio vaccine called Salk used in 1955–1961, which caused recipients to become infected with the monkey virus SV40. Regarding the oral polio vaccine variant used in Congo, its creator Hilary Koprowski said that "if, indeed, somebody were to poke his nose into the live virus vaccine, he might find a non-polio virus in all the preparations currently available."

Given these risks, no country volunteered to test the experimental oral polio vaccine on their own population. But Belgium offered to have it tested in Belgian-ruled African territories, and a large-scale vaccination trial took place there in 1957–1960. The earliest confirmed case of HIV is from 1959 at one of the vaccination sites.

The gist of the OPV hypothesis

The main claim of the OPV hypothesis is that the OPV vaccines used in the 1957–1960 trial (called “Chat”) were developed on site in a large laboratory in Stanleyville in Belgian Congo, using chimpanzee kidney cells. If that did indeed happen, then it’s possible the virus crossed over from chimps to humans through the vaccine.

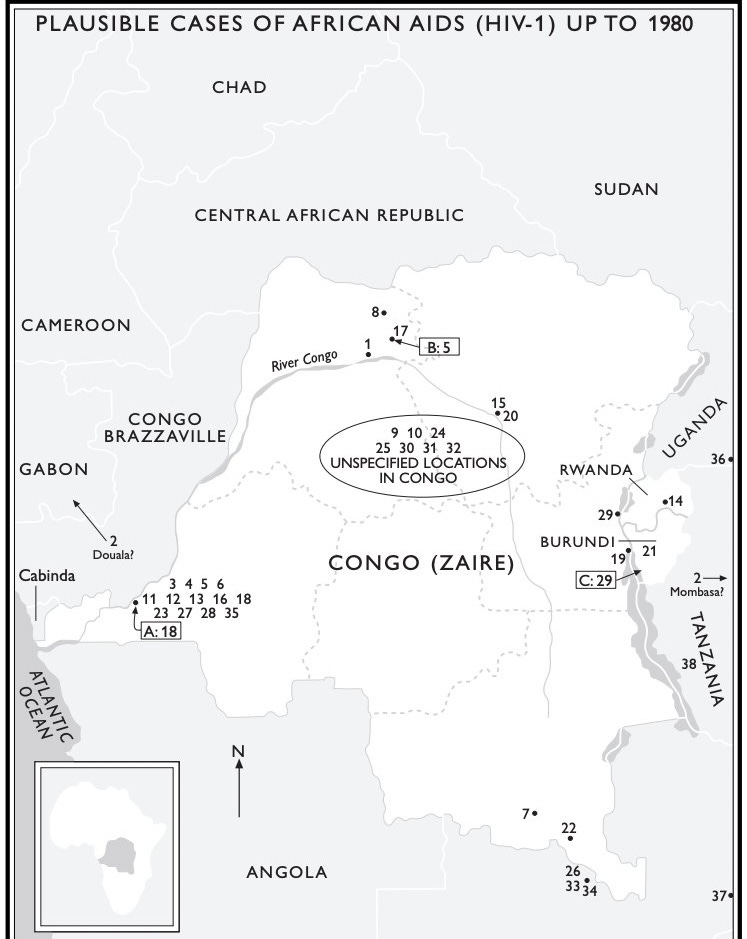

The earliest identified HIV cases are from 1959 and 1960, from the regions where the Chat vaccine was administered. In fact, the locations of all the earliest cases overlap substantially with the location of the vaccine sites.

A and C mark the locations where most of the earliest cases of HIV have been identified; 18 and 29 cases respectively. (The other numbers are IDs of individual cases.) A is Kinshasa, where 76,000 people were vaccinated, the largest campaign at a single site. C is the Ruzizi valley, where over 200,000 people were vaccinated. Note that while Kinshasa is a larger city, the locations in the Ruzizi valley included smaller towns and villages, which would not be expected to be early epicentres of HIV.

The HIV-ancestor virus SIV has existed in chimpanzees for millions of years, and humans have lived alongside chimpanzees in Africa since the origin of Homo sapiens. Hence there was ample time during which a chimpanzee could have bitten a human, thereby allowing HIV to potentially become endemic in humans. Human civilization in central Africa also stretches back at least a thousand years. If the OPV vaccine and HIV emergence are not connected, it would be a significant coincidence that the virus only took hold in humans around the time of the Chat vaccine.

In fact, there are several improbable coincidences the bushmeat hypothesis must explain:

HIV did not take hold in humans for all of history and pre-history, until the time of the Chat vaccine trial.

When HIV did take hold, it was in locations that overlap substantially with those where the vaccine was administered.

There are several variants of HIV, each of which would have required separate cross-species transmissions. This, of course, makes the coincidence even more improbable. Why did a crossover event not take place for all of history, and then take place several times within a short timespan?

Most versions of the bushmeat hypothesis claim a crossover event several decades prior to 1959, after which mutations would accrue. Thus, there should have been many HIV cases between this year and 1959. Yet none have been identified.

How plausible you find the OPV hypothesis depends to a large extent on how you think about such coincidences. I have noticed that many people regard this type of evidence as a separate category, and not as "real" evidence – regardless of whether the improbability of the coincidence increases by a factor 2 or a factor 10. "The crossover had to happen sometime, why not then?", people will say. This is a way of thinking I do not share. I think that if a hypothesis requires an extraordinary coincidence in order to be true, then there is significantly less chance that it is true.

The legendary biologist W.D. Hamilton shared my way of thinking. While he thought that there was no proof either way, by weighing up all the evidence, he estimated that there was a 95% chance the OPV hypothesis was true. His main reservation was that at the time it was thought a case had been identified from before 1957. This would have disproven the hypothesis. However, the case later turned out to have been caused by laboratory contamination with a modern HIV virus.

It is also worth considering the straightforward plausibility of this hypothesis. The polio vaccines in question were cultured using chimpanzee kidney cells, which are known to harbor SIV, the HIV-related ancestor viruses. It is known that the vaccine production methods of the time would not have been able to completely eliminate such contaminating viruses. The potentially contaminated vaccines were subsequently administered to a large number of infants. This last fact is significant because it is often challenging to transfer a virus from one species to another. When scientists attempt such cross-species viral transmission in laboratory settings, one approach has been to use infant animals, as their immature immune systems are more susceptible to viral infection. In 1990, Louis Pascal wrote an article describing these factors, stating that "if one were attempting to start a human epidemic of an animal disease, one could scarcely do any better than feeding multiple unknown viruses from our closest biological relatives to many millions of infants".

The OPV hypothesis has been debated for a long time. In 1985, scientist Cecil Fox tried to find and test early lots of the Stanleyville Chat vaccine, without success. In 1990 Louis Pascal wrote the above-mentioned article describing the hypothesis, and in 1992, the story went mainstream when it was featured in Rolling Stone magazine. Afterward, the journalist Edward Hooper became interested in the hypothesis, and wrote a book about it in 1999, called The River. This book is freely available on his site. The book is very detailed (it is the source for the map above). Following this work, several articles were published addressing the hypothesis, claiming to have refuted it.

Claims of refutation

The OPV hypothesis is said to have been refuted multiple times. (Wikipedia describes it as "a now-discredited hypothesis".) Let’s go through the claims:

Claim 1: The Chat vaccine has been studied many times, and no HIV-related virus or even chimpanzee cells have been identified.

To me, this represents confused thinking. The OPV hypothesis states that the samples produced in Stanleyville were made using cells from chimpanzees, which were contaminated with the virus. The hypothesis is not that Chat vaccines produced elsewhere in a different way were also made using chimpanzee cells, and therefore also be contaminated with SIV. As of today, there has been no test of the Chat vaccine used in the 1957-1960 trial in the Belgian Congo.

Claim 2: Chimpanzees were not used in the production of the Chat vaccine used in the 1957-1960 trial in Congo.

This has been claimed by the inventor of the Chat vaccine. However, the 2004 documentary ‘The Origins of Aids’ provides solid evidence that chimpanzees were indeed used. (It is currently freely available on Youtube.) There are interviews with previous staff and researchers, all affirming that chimpanzees were used. There is even film evidence of chimpanzees at the site. The documentary goes into extensive detail about this, and is a recommended watch.

Claim 3: The chimpanzees in the area near Stanleyville did not carry the right variant of the virus.

This is not correct, as Hooper explains on the Aidsorigins website:

There is documentary evidence that at least one Pan troglodytes troglodytes (Ptt) chimpanzee from the west central African region that includes Cameroon was present among Koprowski’s chimps in the Congo. (In reality, there were probably several such Ptt chimps present, but the one single documented chimp proves the point.) Because these chimps were co-caged and group-caged together, an SIV introduced by one single chimpanzee could have infected many others in the camp. For the OPV theory to work, it requires only one such SIV-infected chimp to provide kidney cells or sera that were used in the vaccine.

Note that this objection also spells trouble for the bushmeat hypothesis. If chimpanzees with the right variant of the virus are far from the Congo, it is certainly odd that no earlier cases have been found close to the source of the virus.

Claim 4: Phylogenetic analysis shows that the last common ancestor of HIV strains dates to 1940 or earlier.

If you make assumptions about the rate of change in the virus, you can look at the differences between strains and use this information to estimate the date of their last common ancestor – a standard method in evolutionary genetics. Multiple papers have done this, and all arrive at dates earlier in the 20th century, well before the Chat vaccine. Assuming their assumptions hold, this means that the pandemic could not have sprung from a single variant from around 1958.

However, their assumptions about the rate of change do not hold for HIV. The problem with the “molecular clock” estimation approach is that while it works well for DNA viruses, it does not work well for RNA viruses like HIV – which evolve to a remarkably large degree by recombination. Recombination can introduce a larger amount of genetic variation in a single event than point mutations. This, in turn, results in a different apparent rate of change in the viral genome when compared to the accumulation of single mutations over time. A paper by Mikkel Schierup and Roald Forsberg, Recombination and phylogenetic analysis of HIV-1, states that for HIV "it is not valid to use a phylogenetic method to obtain the time estimate."

What’s more, the claim is only an argument against the OPV hypothesis if you assume that there is an index case infected with a single variant of HIV. (If the bushmeat hypothesis is correct, that would be the most likely scenario.) But under the OPV vaccine hypothesis, it is plausible that multiple variants of the virus were present in the chimpanzees and, therefore, in the vaccines. It would then be no surprise to find early strains of the virus with different mutations in them. They would have a last common ancestor in chimpanzees some time earlier, which is natural.

Worobey and the lab leak

It is noticeable how many similarities there are between the debate over AIDS origins and the debate over COVID origins. In both cases, we have a pandemic that started in a highly coincidental time and place (assuming zoonotic causation). And in both cases, we have widespread attempts to discredit the hypotheses and to slander proponents as "conspiracy theorists". Mention of the COVID lab leak hypothesis was previously removed from Wikipedia, and is even today only mentioned as something "not supported by evidence", in contrast to the "scientific consensus" of zoonotic origin.

A further interesting similarity is that the researcher Michael Worobey is a central figure in the claimed refutations of both hypotheses. Regarding COVID, Worobey was co-author on a paper with Edward Holmes claiming that lab leak origin was highly unlikely. And he was first author on a paper about the Huanan Seafood market being the early epicenter, initially claiming that it constituted "dispositive evidence for the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 via the live wildlife trade". This paper has been widely criticized for its statistical approach and lack of attention to ascertainment bias. Regarding AIDS, he is the author of publications claiming to have refuted the OPV hypothesis, both the one advancing Claim 3 and the one advancing Claim 4 in the list above.

Perspectives

If the OPV hypothesis is correct (it may not be), it is worth considering what the relevant researchers have caused in Africa and the world: tens of millions of deaths from related illnesses, not to mention large-scale suffering. The people of Congo have endured a series of tragic events: brutal exploitation under King Leopold's colonial rule; being forced to take a vaccine that may have caused AIDS; followed by the devastation of the Congo civil wars.

It’s also important to reflect on the problem of scientific hubris. Today, vaccine production is under much stricter control, and contaminated viruses are very unlikely to survive the production process. Therefore, we do not really need to worry about a vaccine crossover event occurring again via this mechanism. However, there may be other scientific endeavors in which greater caution is warranted, given the extreme cost of mistakes such as this. Gain-of-function research is one.

A slightly different version of this article was originally published on Twitter/X.

Jonatan Pallesen has a PhD in statistical genetics. He is currently writing a book titled Intuitive Statistics.

Consider supporting Aporia with a paid subscription:

You can also follow us on Twitter.